- Home

- Tanya Anne Crosby

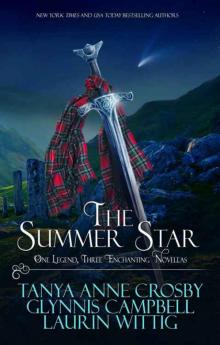

The Summer Star: One Legend, Three Enchanting Novellas (Legends of Scotland Book 2) Page 7

The Summer Star: One Legend, Three Enchanting Novellas (Legends of Scotland Book 2) Read online

Page 7

“Aye lass.”

“What a sad lump,” Sorcha said in her pique. In fact, in all her life, she had never met a more beautiful man who’d so clearly lost his will to live.

“’Tis precisely why we need you.”

Sorcha exhaled a sigh. Her soft heart might, in truth, be the death of her yet, but the thought of that poor man lying upstairs, his face to the wall, his back to the door, and his shoulders shaking ever so slightly, made her feel heartsick. To be sure, it was a tragedy, and no matter how furious she was with her brothers and her sisters, she would die a hundred thousand deaths if she ever harmed a single one, much less lopped off their heads.

But how strange, for they couldn’t have known Sorcha had any experience with this type of ailment… could they? Her brother’s wife was blind, as well. Constance was traumatized by the collapse of their mountain—the very same accident that supposedly took Una’s life. Except that, Constance was still blind, and neither Sorcha nor Lìli had been able to cure her. They had tried every potion in their repertoire: tinctures, elixirs, salts, and more. In the end, they had simply begun to teach her that her blindness wasn’t an end to her life and she had far more to offer than her eyes alone might allow.

“Sweet girl, we beg you… please. If you would be so kind as to aid our laird, we will reward you handsomely for the effort.”

“But all I want is a boat to take me to the Isle of Skye. And my horse since, by the by—” She shot Alec a baleful glance. “—you did not fulfill your end of the bargain. And yet, if, in fact, I should agree, and if your laird should regain his sight before May Day’s Eve? Then will I be free to go?”

Alec looked at Bess, and Bess looked back at Alec, and for the longest time, neither of them dared to look at Sorcha. But, at last, Alec relented, “Yeah. Verra well. Heal our laird an’ ye’ll be on your way.”

Chapter 7

In a modest inn along the king’s road, sat a wee woman with a dirty patch over one eye and hair as white and wiry as a bird’s nest. She sat pleasantly, biding her time, drinking slowly from a tankard of ale. Cool air blustered in as the door opened, and she straightened her back as six liveried men sauntered in, wearing the sigil of their house: twin black ravens beating their wings against a sword between. These were Padruig Caimbeul’s henchmen, and more oft than not, if they were searching for a body, it boded ill. However, whereas the innkeeper cringed at the sight of these men, the old woman sat bright-eyed. Neither did she cower when they went about, all cock and brag, scaring good paying folk out the door. They were asking, “Have you seen a girl? Dark hair, traveling alone? Answers by the name of Sorcha?”

“Nay,” said a frightened man. He gathered his belongings and gave a wary glance toward the hapless innkeeper. “I’ve seen no one—I swear it!”

“Nor I,” said another, and he too, made to leave.

It was highly unlikely to find women alone in such an establishment, unless they be harlots, and yet, the old crone sat, undaunted, unafraid to be mistaken for a woman of ill repute. For some men, even toothless old hags were perfectly acceptable by the time their todgers threatened to turn blue. Presently, one of the liveried men sat down beside her. “Have you perchance seen the girl we seek?”

The old woman grinned, showing perfect, white teeth. “The one called Sorcha?”

“Yeah, madam.”

“No,” she said, shaking her grizzled head. But, then, as the man made to rise, she added, “Though I did hear of her…”

Padruig’s man sat again, scowling. “So what did you hear?”

“I have heard that she journeys to the cradle of our kin.” And there was awe in the old woman’s voice as she spoke. She had more to say, but the liveried man furrowed his brow. “What gibberish is that?”

“Ach! Ye’re a fine, braw lad,” the old woman declared. “I can see in your eyes, you’re a wise mon, too.” And now, having settled his ire, he allowed her to continue. “So ye must know ’tis from Rònaigh’s own Giant’s Cave they carved that stone from Scone? Ye know the one, d’ ye?”

“Of course,” the man said. He straightened his back. “An Lia Fàil.”

“That’s the one!”

“King David was crowned upon it, himself.”

The woman nodded. “So, they say.” She reached for her long-gnarled staff beneath the table. “Some say Conn of the Hundred Wars was crowned there, as well, but what should I know? I’m merely an auld woman.”

The man arched his brow. “Quite a lot, or so it seems.” But rather than scold her for her rambling, he meant to return the favor, flattering her instead, hoping to coax more out of her. “So you must be a verra, verra important woman to know so much. Do tell, what else ha’e ye heard?”

The old woman clutched her long staff with twisted fingers. “Oh… naught more.”

Cursing beneath his breath, the soldier once again made to rise, and once again, the woman stopped him. “Save this…”

Concealing a scowl of displeasure, Padruig’s man sat again, and the woman continued, oblivious to his rising temper. “She’s gone to wed that blind laird, so I hear.”

“Blind laird?”

“The one from Rònaigh.”

“Rònaigh?”

“That’s what some say.” She eyed her near empty glass with undisguised longing.

“Innkeeper!” shouted the man, raising his hand. “Innkeeper, bring this good woman a round of ale.”

The woman put a hand to her breast. “Thank ye,” she said kindly, looking very pleased. “A wee dram does a body guid.”

“An’ ye been drinking a verra long time from the looks o’ ye,” the soldier remarked. “But now tell me, madam, what else ha’e ye heard?”

“Well,” she said. “The laird of Dunrònaigh—he’s a Mac Swein, I believe—I hear tell e’s the rightful heir of Conn Cétchathach.” The innkeeper placed a tankard in front of her, and the woman stopped to take a long, hefty draught, making him wait. Finally, when she was done, she wiped the sleeve of her gown across her mouth and burped. “Anyway, I hear tell the destiny star hast forebode the rise of Conn’s dynasty.”

“The destiny star?”

“Aye, you seen it.” She pointed to the door. “There be an auld song goes like this… ‘Come the destiny star rising o’er the Minch—”

The man rose from his seat. “A pox on ye, auld hag! I dinna have time to listen to silly auld songs. If’n ye got naught more to share, we’ll be on our way.”

The old woman appeared disappointed, and her chin grew long. “Ach, well,” she said. “Hie thee away i’ ye must, only be sure to follow that star. An’ ye’ll see,” she said. “Ye’ll see,” she said again. “Oh, and be certain to bring a gift for the bride.”

“Devil take ye, woman! I’ve heard quite enough,” said the man, slapping his hand on the table.

And then he rose, without bothering to say goodbye. To the innkeeper’s relief, he gathered up his men and marched back out the door, leaving the inn, for the most part, the way they found it, sans a few good, paying customers. The innkeeper cursed roundly, but the woman smiled, tipping her tankard back one last time, before setting the cup down. Then she retrieved her long staff from beneath the table, and took her leave, following Caimbeul’s men out the door, singing her ditty:

“Come the destiny star rising o’er the Minch,

leading a sweet maid through the mist.

With lang, saft hair and skin so fair,

she’ll tempt a lion from his lair…”

After considering how desperate these people must have been to aide their lord, Sorcha was far more inclined to forgive them. It was a failing of hers, she realized—one her brother Keane had so oft warned about.

“Sorcha,” he’d said. “Your saft heart will be your undoing.” And so here she was, wasting away on a remote little isle in the far northern reaches of the north most Sea, while Una was off and away, someplace else. And nevertheless, it did feel good to have a momentary distraction. Only now that So

rcha had something “other” to think about did she realize how much her fury had enervated her. She didn’t really want to loathe her kindred. She didn’t want to be angry at Aidan, or anyone else. Forsooth, she couldn’t change the fact that she was a daughter to a demon, but she didn’t have to be a demon herself. How could she say nay to people in need?

Resolved to make the most of the occasion—and to be away as soon as possible—she marched over to the stables to visit Liusaidh. No one stopped her as she departed the kitchen. No one ignored her either. She was greeted by exuberant waves and wide smiles as though these people had known her an eternity.

Clearly, Sorcha was free to come and go as she pleased, and, according to Alec and Bess, whatever she needed to aid her—anything at all—she needed only to ask.

Right now, she only wanted to see her darling mare, and she didn’t have to look hard. She found Liusaidh locked away in a dark stable, munching on old hay, surrounded by curious children, poking their little fingers into the stall. But the instant they spied Sorcha, they moved away to allow her passage.

“I ha’e ne’er seen a faerie horse,” said a girl, and Sorcha smiled, patting the child atop the head. “She’s no faerie horse, dearling. She’s a Guardian’s breed.”

“Aye, well, me minny said she’s a faerie horse, an’ I must believe her.”

“Must ye now?”

“Yeah.”

There was little sense in arguing with a tot. If the round-faced cherub wished to believe Liusaidh was a faerie horse, so be it.

Amused, Sorcha moved into the stall, closing the door behind her. She caressed Liusaidh’s cheek, whispering softly into her ear. “Dinna worry, lass,” she said. “We’ll be on our way soon enough.” Little more than a fortnight, if Sorcha had it right. Already, they were preparing for the festival that would signal the end of Sorcha’s prison sentence. However, Liusaidh need not spend her days locked in a tiny stall. Back in the Vale, they did not keep their horses trapped in dark stables. The minute she could, Sorcha intended to set her horse free to run. Liusaidh was far more accustomed to roaming the fields.

Sadly, in the next stall, stood a dark horse, with an equally dark mood. As the only other horse in the facility, Sorcha was quite certain it must belong to the laird. Head down, the auld boy seemed a bit despondent, like his master. Perhaps he too would enjoy a romp in the fields, along with Liusaidh? Regardless, she was certain his master had not visited him in far too long. “What is that horse’s name?” Sorcha asked the children.

“Diabhal,” answered an older boy.

“He is Caden’s,” said a girl. “Will ye fix him?”

“The horse?”

“Nay!”

The children all squealed with laughter.

“She means our laird,” explained the boy.

Sorcha turned to address the motley crew of children. With dirty little faces and pink noses, they all waited expectantly for Sorcha’s reply.

Certainly, she was going to try to fix Caden, but she couldn’t promise. And yet, the hopeful looks on their faces were so earnest Sorcha daren’t disappoint them. “Yeah, I will,” she said, and prayed it could be true.

One boy came forward, holding in his hand a crushed yellow blossom. He handed the tribute up and over the gate. “Here,” he said. “It’s for ye.”

“Tapadh leat,” Sorcha said. Many thanks.

“Auld Biera said to gi’ it to ye,” the boy explained. “She said ye would ken how to use it.”

“Did she now?” Sorcha asked, inspecting the crushed flower. It was a blossom of the ruagaire deamhan —the demon chaser, aptly named because it chased away evil spirits—those at large, and those inside a body. It bloomed most profusely around the summer solstice. The crushed blossoms, when steeped in oil, turned the tincture blood red. It could be used to staunch bleeding, bind wounds, or even to counteract poison. However, when taken internally, after being steeped in purified water, it had a calming effect on the body. Una had introduced her to the flower, and was partial to its healing powers. Once, when Sorcha was ten, she’d taken her up to the faerie glen near Dubhtolargg and showed her how to pick and prepare them.

Hmm…. the more she knew of this old woman called Biera, the more she suspected it could be Una by another name. However, rather than covering her tracks, her mentor seemed to be leaving her clues. “Can you show me where this blossom grows?” Sorcha asked the boy. He nodded, and she came outside the stall and took him by the hand. “Will you show me now?”

“I will,” replied the little girl. “I will!”

“Me too,” said another child, and they all vied for Sorcha’s free hand. By the time she left the stables, she had a tiny hand in each of hers and half a dozen little fists gripping her by the gown.

Chapter 8

With only a smattering of warriors remaining, and mostly women and children left to defend the keep, the village of Rònaigh had weathered the winter with trepidation. And now if the prophecy foretold by the holy woman was true, now was the hour of their greatest vulnerability. Biera had said she would be the one who would lead them away—that girl with the long soft hair, who now walked hand in hand with their younglings, a number far outweighing living adults. It would take the entire village to raise them. And nevertheless… unless Sorcha fulfilled the seer’s prophecy, their time on this earth would be short. So much depended upon her tutelage of Caden. All the more depended upon the death of Caden’s pride. When came the time… and soon… Bessie prayed with all her heart Sorcha would prevail. She knew very well that Alec would have taken no joy in the stealing of an innocent, particularly after the ordeal with Auld Macleod, but all their hopes rested upon Sorcha’s shoulders.

Stealing a moment together, the two faithful servants watched from the window as Sorcha went traipsing up the hillside with their children. Under the bright light of day and that strange luminous star, she looked divine in the gown Bess had given her to wear—the bride’s dress that once belonged to Caden’s minny. Even taller than Mary Mac Swein had been, the dress swung about Sorcha’s ankles as she walked. “D’ ye think she can do it?”

Biera had been so sure, but Alec looked worried. He shrugged.

“She didn’t like my bread,” Bess said, with a sigh. “Nobody likes my bread.”

Alec turned to face her. “Ach, lass, she was merely despondent o’er the news. Dinna fash yersel’ o’er it. I love…” He seemed on the verge of saying something more. “Your bread,” he said at last. “I love your bread, Bessie dear. I love your bread so much that it pains me.”

Left with no bairns after her husband’s death, Bessie was eager to please. She had been doing what she could to fill the old cook’s shoes and she wanted desperately to win Alec’s heart. “Would ye like some now? I have three loaves remaining.”

“Uh, yeah,” he said, smiling awkwardly, although he kept her hand in his as he turned back to the window.

Bessie dared to hope he shared her affection. Boldly, she laid her head against his shoulder, as they watched the children lead Sorcha up the hill, to the place where so many of Rònaigh’s lives were lost that terrible day last November. But, how curious, she thought… all those little yellow blossoms had appeared precisely where so much of Rònaigh’s blood was spilt. “What di’ she say that flower was?”

“St. John’s Wort, named for the decollation of Saint John the Baptist.”

“Who is Saint John, and what is a Baptist?”

“I dunno, Bessie. But I think it must be someone important.”

“Ach, then, we shall have to ask the priest when he returns. Although I dinna think it will be soon, after Caden threatened to hang him by his tongue after he told him the blindness was a curse from God.”

They had a passel of priests who came to Rònaigh now and again, mostly to visit the Shrine of St. Ronan. All holy men and women were welcome to their isle, where many believed lay the cradle of life itself, for it was here the Christian god met with the church of Éire, and the faith and

fury of the North Men.

On the north side of their island was a druid circle, a sacred landmark where they held the yearly May Day festival. And further north, on the opposite end of the summit, lay the ruins of an old church built by St. Ronan—a monk who’d had foresight to see the divinity of Rònaigh. For as long as there was memory, these sacred places and stories had been a part of their lives. The holy woman said they were a chosen people.

“But it’s curious,” Alec said. “Dinna ye think? A blossom named for a beheaded saint, now meant to heal the heart of a man who took his brother’s head?”

“What if she’s wrong…?”

Alec turned to draw Bess into his arms. “Ach, sweet lass. If she’s wrong, Rònaigh will be lost.”

For a long, long moment, neither so much as blinked, and then Bessie dared to lean into his embrace, turning sad brown eyes up to Alec’s face. “Pray, then. Pray the girl must succeed…”

“Bessie… I… I need to say something…”

“What?” she asked, pleading for the words she longed to hear. Her heart kicked a beat against her breast. And then, suddenly, the sound of Caden’s voice roared throughout the keep. “Oh, my!” she exclaimed, and Alec squeezed her one last time before rushing away.

Caden could no longer spy the cracks in his ceiling, but he could damned well hear the wind wailing through them. His eyes seemed to have languished, but his ears grew keener by the second.

Shortly after the… blindness, he’d ordered everything removed from his chamber—everything—all his weapons, all his belongings, even the brazier that was meant to keep him warm. He’d grown tired of tripping over his trunks and singeing the hairs of his arse. Only the bed and one chair remained, and if he shivered in the middle of the night, it was just penance for all he’d done.

Lord of Shadows (Daughters of Avalon Book 5)

Lord of Shadows (Daughters of Avalon Book 5) To Love a Lord: A Victorian Romance Collection

To Love a Lord: A Victorian Romance Collection The Daughters of Avalon Collection: Books 1 & 2

The Daughters of Avalon Collection: Books 1 & 2 The Impostors: Complete Collection

The Impostors: Complete Collection The Holly & the Ivy (Daughters of Avalon Book 2)

The Holly & the Ivy (Daughters of Avalon Book 2) A Winter’s Rose

A Winter’s Rose Fire Song (Daughters of Avalon Book 4)

Fire Song (Daughters of Avalon Book 4) Elizabet

Elizabet Kissed; Christian

Kissed; Christian Once Upon a Knight

Once Upon a Knight Viking: Legends of the North: A Limited Edition Boxed Set

Viking: Legends of the North: A Limited Edition Boxed Set Five Unforgettable Knights (5 Medieval Romance Novels)

Five Unforgettable Knights (5 Medieval Romance Novels) Meghan: A Sweet Scottish Medieval Romance

Meghan: A Sweet Scottish Medieval Romance Reprisal: A Prequel Short Story to REDEMPTION SONG

Reprisal: A Prequel Short Story to REDEMPTION SONG Highland Song

Highland Song The Summer Star: One Legend, Three Enchanting Novellas (Legends of Scotland Book 2)

The Summer Star: One Legend, Three Enchanting Novellas (Legends of Scotland Book 2) Once Upon a Kiss

Once Upon a Kiss MacKinnons' Hope: A Highland Christmas Carol

MacKinnons' Hope: A Highland Christmas Carol The MacKinnon's Bride

The MacKinnon's Bride Highland Brides 04 - Lion Heart

Highland Brides 04 - Lion Heart A Perfectly Scandalous Proposal (Redeemable Rogues Book 6)

A Perfectly Scandalous Proposal (Redeemable Rogues Book 6) Reprisal

Reprisal Maiden from the Mist (Guardians of the Stone Book 4)

Maiden from the Mist (Guardians of the Stone Book 4) Tell No Lies

Tell No Lies The King's Favorite

The King's Favorite Meghan: A Sweet Scottish Medieval Romance (Sweet Scottish Brides Book 2)

Meghan: A Sweet Scottish Medieval Romance (Sweet Scottish Brides Book 2) The Impostor Prince

The Impostor Prince Happily Ever After

Happily Ever After Sophie's Heart: Sweet Historical Romances

Sophie's Heart: Sweet Historical Romances Viking's Prize

Viking's Prize Page

Page Angel of Fire

Angel of Fire Once Upon A Highland Legend

Once Upon A Highland Legend Highland Brides 03 - On Bended Knee

Highland Brides 03 - On Bended Knee Sagebrush Bride

Sagebrush Bride Lyon's Gift

Lyon's Gift Lady's Man

Lady's Man The King's Favorite (Daughters of Avalon Book 1)

The King's Favorite (Daughters of Avalon Book 1) Highland Storm

Highland Storm Redemption Song

Redemption Song Three Redeemable Rogues

Three Redeemable Rogues