- Home

- Tanya Anne Crosby

A Winter’s Rose Page 19

A Winter’s Rose Read online

Page 19

They were, indeed… two sleeping miracles, and Rosalynde might have been content enough to stand and stare at her nephews for hours longer… but she heard a horn blast, and a stab of fear entered her heart.

Elspeth started, her eyes widening, and she said breathlessly, “Malcom!”

Chapter 29

Not only had the lord of Aldergh not returned from his council at Carlisle, Giles was gone now, as well. With the steward’s permission, he’d requisitioned two men from Aldergh’s garrison, and before leaving, presented the reliquary and grimoire to Cora’s husband for safekeeping, explaining that the items were priceless, and every care should be taken to safeguard them. In turn, Alwin presented the items to Cora and Cora handed both the book and reliquary to Rosalynde, looking perfectly confused over their value. To her undiscerning eyes, the reliquary would seem to be little more than a brass bauble, and the book must have appeared a dirty volume with the look of a Holy Writ, only with yellowed pages and vellum that was already cracked and blackened with age.

Her heart tripping with the news that Giles had so easily departed—essentially abandoning her at Aldergh—Rosalynde took the book and gave it to her sister.

At least the book was safe, and truly, that’s what mattered, she told herself, and yet, her heart felt as though it might be rent in two, and Giles still had the lion’s share.

Despondent though she was, she understood Elspeth’s intake of breath as her fingers touched the sacred volume. Its hallowed pages must be more than five hundred years old, but the spells and recipes held therein were easily a thousand or more. Not since Elspeth was a small girl had she laid eyes upon their grandmother’s grimoire, and, in truth, until they’d arrived in London, none of the sisters had ever even looked upon it. Only Elspeth had ever had the chance to hold it and open it, under the supervision of Morgan Pendragon.

“We must keep it safe,” Rosalynde entreated. “On pain of death. Mother must never see the Book of Secrets again.”

“I have precisely the place to keep it,” Elspeth reassured, and then led Rosalynde to her salon, to a corner of the chamber, where the floorboards were loose. She lifted a board, and set the book beneath, then replaced the floorboard, and peered up at Rose while still on her knees, her blue eyes full of concern. And it was in that instant Rosalynde weakened.

Tears sprang to her eyes—tears she could no longer deny. “He’s gone, Elspeth,” she said, her face twisting with grief.

Her sister’s brows slanted unhappily as she rose to her feet, embracing Rosalynde, putting her warm, comforting arms about her. “Here, here,” she said. “I am here, Rose. Do not fret. I am here.” And she let her sister comfort her, sinking like a hopeless child into her consoling arms.

So many weeks she’d traveled to arrive here, so much peril she’d endured—she and Giles both together. But now he was gone. Gone. And he had ridden away to see to his own affairs without so much as a bittersweet so long.

Carlisle Castle lay but an easy half-day’s journey from Aldergh. The jewel of Cumberland was impossible to miss, with its fiery red stone and enormous girth.

Having gathered his most trusted advisors to discuss his new stratagem—a possible siege of York—the King of Scotia was in residence, sequestered behind closed doors. Giles needed only present his Paladin sword, with the serpentine emblem, and he was admitted at once.

Without a word, he took an empty seat among the men gathered, and listened quietly as the Scots king carried on about the strengths and weaknesses of York and the benefits of controlling the archdiocese there. Already, he held Bamburgh, Newcastle and Carlisle and Giles suspected that, if he could, he would bring the entirety of the ancient kingdom of Northumbria under his dominion. Regrettably, he would soon learn that the Church would not sanction this plan. There was already a plan in motion, and it did not include negotiations with yet another contender, regardless of David’s intentions or associations.

David of Scotia was well respected by the Church, else he’d never have been brought into the inner sanctum, but that didn’t matter. And now that Rosalynde and her book were both safe, he had a job to see to, and, knowing what he knew now, there was all the more at stake—not merely the fate of a northern estate, or even a kingdom.

As God was his witness, he’d never coveted Warkworth for the sake of a title. His father had earned the lands through sweat and blood. He’d answered every call to arms by King Henry, and he’d raised his sons to honor England and its God-appointed sovereign. And even after Stephen usurped the throne, Richard de Vere had been prepared to keep the King’s peace. It wasn’t until very recently that he’d turned his eyes toward the Empress, aligning himself with Matilda, and Giles had had a hand in that matter. When the Church asked him to approach his sire in the name of the Empress, he had done so without reservation. He had convinced the elder de Vere to join their cause. This, after all, was why Wilhelm was sent to Arundel, in order to convey their father’s answer to Henry’s widow, who secretly passed his answer to Matilda. Giles suspected that Lady Arundel’s husband discovered the correspondence and immediately dispatched one of Morwen’s ravens—those bloody aberrations. It would have flown directly to its master, not to Stephen, and unfortunately for Warkworth, Morwen and Eustace had been only a few leagues from Warkworth when the message arrived. After his resounding defeat at Aldergh, the king’s incompetent son had endeavored to assuage his puerile ego by teaching the wayward lord of Warkworth a lesson, putting his “adulterine castle” to the torch, with innocents still asleep in their beds. Ultimately, Giles felt responsible for the entire ordeal, and if it were possible, he would have handed Warkworth to his brother lock, stock and barrel.

Right now, he needed the lord of Aldergh’s help, but evidently, this was no longer a matter of one defender of the realm appealing to another. Malcom Scott was no longer Stephen’s man… he was David’s—quite clearly, because here he sat, divulging York’s weaknesses and expounding upon the complications of wresting York from the English. And yet this was far more complicated than even Malcom realized.

Although William FitzHerbert, the king’s nephew, had been deposed and the succession to the archbishopric was still in question, the Pope had yet to decide between Henry Murdac and Hilary of Chichester. The king’s choice was Hilary and he had already endeavored to deprive Murdac from taking up residence in the city of York, but he was currently negotiating with the pope. He would give Murdac the archbishopric if only the Pope would agree to coronate his son. The Pope was not in the frame of mind to do so, and yet, neither would he accept a third candidate for the archbishopric, when he had already decided upon Murdac. At the moment, a siege of York would be met with opposition, not only by Stephen, but by the Church as well.

Considering how best to proceed, he waited patiently for his opportunity to speak, then put forth a request: He needed stone to rebuild. He would pay well, and because Warkworth lay so close to the Scots border, he sought the Scots king’s blessings. But, of course, David saw an opportunity and seized it. He offered Giles the chance to retain his title… if only he would give his allegiance to Scotland instead of England. If he should agree to it, he could have all the stone he needed without question, and there would be no risk of losing his lands or, for that matter, his title. David would confer it to him now, on the spot.

A shocked murmur swept through the council. For all that these fools knew, Giles was a younger son of a lowly baron, with no experience and scarcely any influence. It was unthinkable what David had proffered, and yet… Giles could not and would not accept. He shifted in his chair, ill-at-ease, because there was so much he hadn’t leave to say, and the council room was filled with too many curious ears. His gaze skittered down the table, from man to man, resting for a moment on the lord of Bamburgh, whose youngest daughter was wed to his father, and died by Eustace’s hand. There was no love lost between their houses, despite the familial alliance, because Bamburgh bent the knee to David. But for Giles, this was inconsequential.

In essence, he was only reclaiming his father’s seat by behest of the Church. And if they had not ordained it… he would still be wielding his sword in whatever capacity they demanded. That he was now a lord of the realm—an Earl for the time being—did not come without obligation. There was only so much he could bargain with and keep the spirit of his oath.

He chose his words carefully. “I do not need warriors, Your Grace. I have warriors. I need stone, and whatever men would be required to convey and work the stone. It is my intent to restore Warkworth to a defensible state as swiftly as is humanly possible—most certainly before I am expected to return to London and bend the knee to Stephen.”

“Do you plan to forswear your oath to Stephen?” asked David quite shrewdly.

Giles said naught, for there was naught he could say. He picked at a bit of dried foodstuff encrusted upon the table.

“It sounds as though you mean to forswear England, and if so, who else would you bend the knee to, but David?”

Giles flicked a glance at the lord of Bamburgh but didn’t answer the man. His gaze returned to David.

More than any man present, Giles knew that David understood the significance of his Papal commission, and yet David mac Maíl Choluim was king, because he pressed his advantages when he saw the opportunity. “Whatever the case, I haven’t men to spare,” he persisted. “And yet… I would offer… if only you bend the knee to Scotland.”

Giles shook his head, his eyes never leaving the king’s. “I cannot give what is not mine to bestow.”

The tension in the room was marked. In this day and age, few men dared to defy David mac Maíl Choluim. He had risen to such a venerable position. And yet, one man did speak up—a very unexpected ally, and only by virtue of the fact that Giles had arrived with two of his men. “I can spare you whatever men you need,” said Malcom Scott.

His brows colliding fiercely, David shifted in a chair that was made for lesser men, turning to spear Malcom with a disapproving glare. “You have men to spare? And yet, even knowing my plans, you would offer them to Warkworth?”

Giles recognized the hard glimmer in Malcom Scott’s eyes. As would be expected, he was a man not easily cowed. He said, “I have given you my oath, Your Grace, and I mean to keep it.”

“This time,” interjected the Earl of Moray.

“Shut your gob, fitz Duncan!”

Uncowed, Malcom met de Moray’s gaze, and said, “I have given my sword to Scotia, and I will honor my pledge for the rest of my days.” He turned to the King. “Your Grace, would you leave Aldergh without protection, or have me arm bricklayers and quarrymen?”

“Nay,” said the king, waving a hand for peace.

“And yet these are the men I would pledge to my lord of Warkworth, not my warriors.”

The king conceded. “Yeah, times are not so dire as to send bricklayers into the field—have it your way.”

As much as he would like to cede, Giles was forced to disagree. “Do not mistake me, Your Grace. Times, indeed, are so dire…”

Very slowly, the King’s eyes slid back to Giles, his gaze narrowing, “Speak,” he demanded.

Giles shook his head again. “I will not speak aloud what I know, lest you lock me in a tower and call me a madman. And even so, I would advise you to gird your loins.”

“Gird his loins?” wailed de Moray, in protest, clearly not comprehending his cautionary words.

“He means prepare for war, eegit,” said David.

Giles ignored the man. “And nevertheless, Your Grace, I do not need a grant of men. I need stone… and for this I pledge you my word of honor I’ll not join any campaign to wrest the lands you already possess.”

The king’s eyes glittered fiercely. “What of Warkworth?”

“Again, Warkworth is not mine to barter.”

“It is yours,” argued the lord of Bamburgh.

“In name,” returned Giles. “My true oath and my sword belong to the Church, as your King knows.”

David mac Maíl Choluim’s gaze fell to the sword hilt that peeked above the table, a sword that, even now, glowed very faintly with some unnatural light. There were twelve men present at David’s table—and how prophetic that the king of Scotia should have his own Judas. Alas, there was only one way to ferret out a traitor, and so he said, “The Church means to see Duke Henry on his grandfather’s throne and I will do my part to bring that to fruition.”

Giles’s canny dark eyes scanned the entire table, from the lord of Bamburgh to the Earl of Moray, looking for any telltale sign of the betrayer. Unfortunately, the man did not make himself known, and yet, if the sword spoke true, at least one of these allies would carry this news to Stephen, and the Church would know his name.

Perhaps not entirely surprised, David put a hand to his chin, rubbing softly. “Duke Henry?” he said.

“Aye, Your Grace. He is favored above his mother, and should his foray into Wiltshire have proven successful, he might already have been granted an army.”

“And it was not?”

It was phrased as a question, but they already knew what came of that campaign, and for the most part, it came to naught. Giles lifted a shoulder. “His courage did not go unnoticed.”

“He has what it takes. My sister would be proud,” the King said, sounding maudlin, and it seemed, for an instant, that he lingered in some faraway place.

Giles considered the man, wondering why he would favor one niece over the other. “Mary was your sister as well, Your Grace. What engenders pride in one, but not the other. All things considered, both their daughters even share the same name.”

Matilda. Both strong women, fierce as lions. One was wed to a King. The other was wife to the Holy Roman Emperor.

David of Scotia eyed him shrewdly. “I must lend my support to what I know to be right,” he said. “Matilda is Henry’s rightful heir, and nevertheless, I would, indeed, support Duke Henry as I have supported his mother. But… in the meantime… I will not promise to forgo York.”

The two men held gazes.

After a moment, Giles shrugged. “That decision is yours alone to make, Your Grace. Either way, I will not raise my sword to oppose you… and… if you agree to the stone… I will speak your case to the Pope.”

“You have his ear?”

Giles was careful with his words, but said, “I do.”

David nodded, his gaze traveling the length of the table. And finally, he declared, “The stone is yours, so long as you pay its rightful lord. If you have a bargain, who am I to contend?”

And still, there was yet one more matter to be discussed… this one with the lord of Aldergh. “There is… one more thing…”

The King lifted his grey-peppered brows.

“As part of my bargain with Stephen, I am pledged to wed one of Henry’s daughters…” He turned his gaze toward Malcom Scott. “Seren Pendragon.”

Malcom’s brows collided. “My wife’s sister?”

Giles nodded, and once again, David waved a hand in dismissal. “Why should any of that concern this council?”

“Because… I would wed another in her stead… her sister… Rosalynde Pendragon.”

The king looked confused. “Are these not both Morwen’s daughters?”

“They are, Your Grace.”

“I see,” the king said, narrowing his eyes. “You risk much if you are already forsworn.”

“And nevertheless, I will have no other, and it is my desire to be shed of any need for Stephen’s blessings by the time I am expected in London. Therefore, I seek your blessing, for what it’s worth.”

“Again, I ask; why should I concern myself with your bride?” argued David. “You have declared for England. And I cannot be bothered with Morwen’s witchy daughters.”

Giles narrowed his gaze. “Because, Your Grace… whether you acknowledge them or nay, they bear a king’s blood, and so I ask your blessing, as I do the lord of Aldergh’s, because it is a matter of state. And... you are—were—their father’s dearest friend

. You must have known that Elspeth Pendragon was the King’s favorite.”

“Aye, well, I am also responsible for the death of their grandmother, in case you did not realize, and I have no regrets. There are forces at work in this realm that must be condemned.”

“And still, you came to aid us,” reminded Malcom. “It was not me, but my lady wife who called you.”

David of Scotia nodded, and after a moment, he said, “So I did. So I did. Well then, for what it’s worth, you have my blessing. For what it’s worth…”

Giles turned to Malcom. “So then, I have one more concern…do you, perchance, have a priest in residence at Aldergh?”

Malcom’s blue eyes glinted. “As it happens, I do. And, if the lady will have you, you have my blessing as well.”

Chapter 30

For all its lateness, Winter descended upon the north with a vengeance not unlike Morwen Pendragon’s. Bitter winds howled through the old castle, leaving everyone it touched shivering. Rosalynde discovered firsthand what her sister meant about the tapestries. Wherever they were hung, those rooms were warmer, quieter, and cozier—much in the same manner of a warming spell, except that these spells were woven of wool, linen and gilt-wrapped silk.

As it turned out, it was fortuitous for Rosalynde that her sister’s twins were wont to come so early, else she might not have returned in time from Chreagach Mhor. Traveling in this weather would seem impossible, and particularly so with two small babes. As it was, she’d delivered them well, and spent a good month with her husband’s family, before returning to Aldergh.

Lord of Shadows (Daughters of Avalon Book 5)

Lord of Shadows (Daughters of Avalon Book 5) To Love a Lord: A Victorian Romance Collection

To Love a Lord: A Victorian Romance Collection The Daughters of Avalon Collection: Books 1 & 2

The Daughters of Avalon Collection: Books 1 & 2 The Impostors: Complete Collection

The Impostors: Complete Collection The Holly & the Ivy (Daughters of Avalon Book 2)

The Holly & the Ivy (Daughters of Avalon Book 2) A Winter’s Rose

A Winter’s Rose Fire Song (Daughters of Avalon Book 4)

Fire Song (Daughters of Avalon Book 4) Elizabet

Elizabet Kissed; Christian

Kissed; Christian Once Upon a Knight

Once Upon a Knight Viking: Legends of the North: A Limited Edition Boxed Set

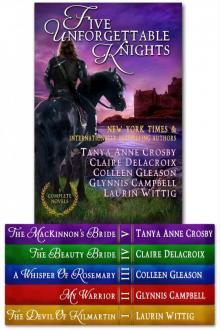

Viking: Legends of the North: A Limited Edition Boxed Set Five Unforgettable Knights (5 Medieval Romance Novels)

Five Unforgettable Knights (5 Medieval Romance Novels) Meghan: A Sweet Scottish Medieval Romance

Meghan: A Sweet Scottish Medieval Romance Reprisal: A Prequel Short Story to REDEMPTION SONG

Reprisal: A Prequel Short Story to REDEMPTION SONG Highland Song

Highland Song The Summer Star: One Legend, Three Enchanting Novellas (Legends of Scotland Book 2)

The Summer Star: One Legend, Three Enchanting Novellas (Legends of Scotland Book 2) Once Upon a Kiss

Once Upon a Kiss MacKinnons' Hope: A Highland Christmas Carol

MacKinnons' Hope: A Highland Christmas Carol The MacKinnon's Bride

The MacKinnon's Bride Highland Brides 04 - Lion Heart

Highland Brides 04 - Lion Heart A Perfectly Scandalous Proposal (Redeemable Rogues Book 6)

A Perfectly Scandalous Proposal (Redeemable Rogues Book 6) Reprisal

Reprisal Maiden from the Mist (Guardians of the Stone Book 4)

Maiden from the Mist (Guardians of the Stone Book 4) Tell No Lies

Tell No Lies The King's Favorite

The King's Favorite Meghan: A Sweet Scottish Medieval Romance (Sweet Scottish Brides Book 2)

Meghan: A Sweet Scottish Medieval Romance (Sweet Scottish Brides Book 2) The Impostor Prince

The Impostor Prince Happily Ever After

Happily Ever After Sophie's Heart: Sweet Historical Romances

Sophie's Heart: Sweet Historical Romances Viking's Prize

Viking's Prize Page

Page Angel of Fire

Angel of Fire Once Upon A Highland Legend

Once Upon A Highland Legend Highland Brides 03 - On Bended Knee

Highland Brides 03 - On Bended Knee Sagebrush Bride

Sagebrush Bride Lyon's Gift

Lyon's Gift Lady's Man

Lady's Man The King's Favorite (Daughters of Avalon Book 1)

The King's Favorite (Daughters of Avalon Book 1) Highland Storm

Highland Storm Redemption Song

Redemption Song Three Redeemable Rogues

Three Redeemable Rogues